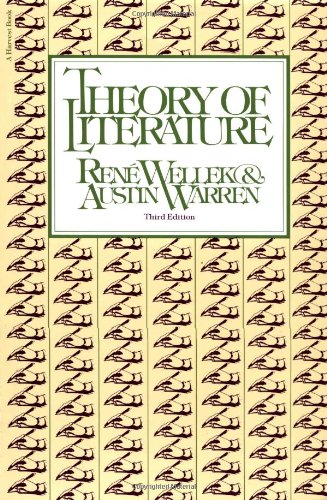

My thoughts on The Theory of Literature by Wellek & Warren

Overview

Title: Theory of Literature

Publishing Year: 1949

Author(s): René Wellek & Austin Warren

Topic and subtopics: Literary studies, literary criticism, Russian formalism, phenomenology,

Synopsis: “Theory of Literature” by René Wellek and Austin Warren provides a comprehensive overview of the major literary movements and theories, such as formalism, structuralism, and phenomenology. It offers readers a thorough understanding of the evolution of literary thought up to the mid-20th century. “Theory of Literature” is considered a foundational text in the field of literary criticism. It’s used widely in academic settings to introduce students to the theoretical frameworks that underpin the study of literature.

Required prereading: classical literature (Shakespeare, Austen, Balzac, Dickens, Henry James, James Joyce, Dostojevski, Gogol etc)

Audience: people interested in Literary Studies

Table of Contents

Author Credentials

René Wellek (1903–1995) was an Austrian-born scholar. After completing his studies at Charles University in Prague, he taught literature in London. After Nazi Germany occupied Prague in 1939, Wellek fled London for the United States. He held teaching positions at the University of Iowa and Yale University.

Austin Warren (1899–1986) was an American literary scholar. He went to Graduate School at Harvard University and received his Ph.D. from Princeton University. Warren held teaching positions at the University of Iowa and the University of Michigan, amongst others.

"- whole milk

- oranges

- chicken nuggets

- chocolate box for A.

- cyanide

..."

Is it now literature?

What is literature and why should you study it?

Wellek and Warren begin the book by diving into questions each scholar should ask themselves before starting research. Why should one study literature? What even is ‘literature’? And how should one study it? These questions might seem basic to many, however, they’ve become very relevant for someone who has had to explain multiple times that literary studies is an actual academic field with hundreds of years of history.

So let’s start with what is ‘literature’. It could be defined as “everything that’s written down”, yet we all agree that a grocery list isn’t literature. (Though, what if it’s written as “-whole milk -oranges -chicken nuggets -chocolate box for A. -cyanide”? Is it now literature?) W&W try to distinguish literature from non-literary forms of expression by discussing the notions of organising the source material, having an intent or practicality, or whether literature has a specific literary language. We could broaden the discussion by adding the beloved questions of current times: “Is listening to audiobooks reading? Is reading an immense amount of non-fiction being a bookworm? Is using AI considered writing?” You see – we’re still asking the same questions just in variations. And no, W&W do not provide a definite answer to our question but rather highlight its complexity.

What is literary studies?

Literary studies are more than just guessing why the poet wrote that the curtains were red. (Most likely the curtains just were red. But maybe it was a premonition of how the heroine would die because of her unhappy marriage?). W&W differentiate three parts that make up literary studies. I will provide the explanation they gave together with how they are understood in present day:

Literary Theory outlines the basic principles of literature. (Based on W&W)

Literary Theory focuses on the theoretical aspects of literature. It asks how we can analyse literary works and phenomena. It breaks the book into smaller structures and analyses the technical devices the author has used (quite possibly unknowingly). But it also examines how readers experience the stories.

Literary Criticism critiques individual works and/or authors. (Based on W&W)

Literary Criticism focuses on how we decide what is good and what is bad literature. It decides most of the award winners (excluding Goodreads and other popularity contests). It’s what ultimately decides what we perceive as the “classics”.

Please note that in some countries Literary Theory and Criticism are used interchangeably.

Literary History outlines the development of literature. (Based on W&W)

Literary History focuses on how literature has changed in time, how history impacts literature and in exchange how literature impacts how we view our past. It also makes sure we have plenty of biographies about authors and their works.

Literary Studies has so much practicality and impact on every reader’s (and non-reader’s) life. Now, I might be biased but I’d say that’s pretty cool.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipiscing elit dolor

Who wrote the story?

In the second part of the book, W&W discuss that before the “ultimate task of scholarship”, analysis, the researcher should authenticate the manuscript and establish the author. It sounds like something you want to say to a student aiming to research pre-20th-century manuscripts. However, with the rise of AI-generated books, is that not the same question we’re facing? Was the book written by the author highlighted on the cover? Was the story or parts of it plagiarised? It seems soon enough we have to focus again on the tasks of “authenticating manuscripts” and “establishing the author”. So maybe it’s good that W&W give us a reminder.

Should the author's life impact your reading experience?

In the third part, W&W debate whether the author’s biography could be used to analyse literature. For ages, scholars have argued whether the author’s real life should have an impact on how the readers perceive their works. Also, vice versa, whether their work could be used to make assumptions about who they are as people. (Those who want to learn more about the subject should read The Death of the Author, an essay by Roland Barthes.) That is a topic I wish more people would familiarize themselves with amidst the constant cancellation of numerous writers. Do J. K. Rowling’s harmful words make Harry Potter worse as a story? Do Colleen Hoover’s questionable actions determine the value of her books? W&W decide that we shouldn’t evaluate the book based on the writer nor make assumptions about the writer based on the book. Indeed nowadays, we have an added layer of financial gain that needs to be considered. How can we read the stories without supporting the people our values don’t align with?

Could you use psychology or other external elements to analyse a book?

W&W discuss in length the possibilities of using psychological analysis in literary study. Ultimately they decide that it could be legitimately used only in the analysis of characters. I have to agree with their decision. Imagine the amount of writers we would need to declare insane only because they wrote about insanity. (And now I remembered authors of crime and horror …)

W&W also agree that literature reflects and influences societal values and norms. However, they argue that viewing the literary work through the lens of philosophy or via other forms of art might not give a significant outcome. For clarity, I must add that W&W couldn’t foresee the rise of live actions so they could not give an opinion on analysing the work through adaptations. Something that is now very common in literary theory.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipiscing elit dolor

Does the story change based on who is reading it?

In the last part of the book, W&W regard the various elements inherent to works of literature. Once more W&W:

a) discuss that a literary work is more than words written on paper (as it might not be even written down);

b) deny that a literary work is the sounds (or meaning behind the sounds) that reveal themselves when one reads the work;

and then they finally dive into the phenomenological and structuralist theories.

(Now, if you read the Theory of Literature and did not understand a word from the twelfth chapter, then congrats! it took me a while to bite through that as well)

The main idea to take from the phenomenological theory is that the mode of existence of a literary work is dynamic and involves an interaction between the work itself and the reader. The meaning and significance of a literary work can evolve over time and through different interpretations. When simplified, just think about the book the 15-year-old you thought was the best book of all time. And coincidentally, your friend did not get it at all. Have you tried reading it again as an adult? Your perception and interpretation have changed, haven’t they?

(My sincere apologies to the phenomenologists for this crude simplification.)

What style means in literature?

If what I covered in last paragraph was difficult to understand, then the thirteenth chapter will make you want to curl up even more. W&W focus on euphony, rhythm, and metre. While these aspects relate more to poetry, they might still be relevant to narrative fiction. However, as someone who’s tone-deaf, the metre will always stay a grey area to me. Leaving music behind, W&W turn to view the language of literary works. They argue that words are more than just the thesaurus definition they carry. They discuss attempts at unique stylistic research, concluding that most of them have been rather unsuccessful. Overall, they recommend examining works through stylistics to establish some unifying principle, or some general aesthetic in a work (or in works of a specific author) or genre. As per their recommendation, it’s become the way we can say that this author’s style is such and such.

Wellek and Warren delve into the significance of images, metaphors, symbols, and myths in literature (after going through various definitions of what they mean). They highlight how these elements contribute to the aesthetic, emotional, and intellectual dimensions of literary works. (The best part of chapter 15 is the explanation of how in the works of John Donne sexuality is religion and faith is love. 16th century Hozier perhaps?) All in all, images, metaphors, symbols and myths shouldn’t be studied in isolation but as an element of the whole work.

What is narrative structure?

Arguably my favourite chapter in the whole book, chapter 17, brings us to the understanding that narrative fiction takes place in its own little microcosm. The microcosm consists of narrative structure, characters, setting, world-view and tone. I believe that this research area of literary studies brings the most benefit to writers and developmental editors. W&W bring out that novels could be written with different structures:

a) either in chronological order,

b) connection via the main character

c) held together by consequences.

They add that when the plot has been properly developed, a change will happen throughout the novel that makes the final situation quite different from the beginning. (I say: Preach!)

After going through various historical explanations of what ‘narrative structure’ or ‘plot’ is, they get to the modern definition that it is the outline of situations and events that constitute the structure of the novel. They go further by bringing in the Russian formalists and Genette’s narratology with their separation of the fabula (or story as it is) and plot (story as it is written). It sounds confusing when you first encounter it, and in fact, the short chapter doesn’t do justice to it. I plan on reviewing some of the books written on narratology and Russian formalism soon enough.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipiscing elit dolor

About genres and authors

Moving away from the deep workings of literary works, W&W discuss the definition and usage of genres. Ultimately, they conclude that the modern theory of genres is descriptive, yet non-restrictive. Meaning we can mix and match the genres as we want. If it wasn’t so then monster smut wouldn’t exist. (And I apologise to those who didn’t know it existed.) In the last chapters, they once more discuss the questions of Literary Criticism and Literary History as I described before. They emphasise that evaluation of literary work should be done based on the work’s own nature, and not based on the author’s practical or scientific intent. I would also add here the author’s personal life and views – you might not like that Brandon Sanderson belongs to a certain church but that is no reason to give the Mistborn series a 1-star review.

In Conclusion

I am a writer and developmental editor who is always in search for books and resources that would enhance my craft. So the important question is: should you read this book?

- If you are interested in Literary Studies, then this is a good place to start at. The book indeed gives readers a thorough understanding of the evolution of literary thought up to the mid-20th century.

- If you are a developmental editor or a book coach, then it would be a good additional material. However, it has little practical value to your work.

- If you are a writer looking for a way to improve your craft, then this is not the book for you. But no worries! There’s plenty of other resources for you.

Nevertheless, I hope you learned something interesting today. I sure did. What resonated the most with me was that the book discusses many questions that are still relevant today.

When reading the book or my overview, what resonated the most with you?

Did I manage to simplify some of the complex ideas for you?

Would you be interested in exploring more books on this topic?

Let me know in the comments!